In the vast chronicle of art history, few names burn as brightly as Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890). He is often conveniently filed under the broad label of 'Post-Impressionism', but such a term barely scratches the surface of his originality, his restlessness, and his defiance of convention. To understand Van Gogh is to place him back into the swirling vortex of late-19th-century Europe, a period of profound intellectual, social and artistic upheaval — and to listen carefully to the urgency in his brushwork, as if it were the pulse of the age itself.

Van Gogh's career was remarkably brief, spanning barely a decade in the 1880s. It was a time when the Impressionists, led by Monet and Renoir, were challenging the stale authority of the academies. They turned away from grand history paintings towards the fleeting play of light and the immediacy of modern life. But when Impressionism reached the limits of what the eye could observe, a new generation began to ask a deeper question: could the canvas hold not just what is seen, but what is felt? Could painting capture the structures of thought, the undercurrents of emotion, the landscapes of the spirit?

This questioning marked the birth of Post-Impressionism — not a unified movement, but a loose constellation of artists including Cézanne, Gauguin, Seurat and Van Gogh, united less by style than by ambition. If Impressionism was about looking, Post-Impressionism was about thinking and feeling. Van Gogh stood at the heart of this shift. With blazing intensity and fearless innovation, he became one of its most recognisable and influential figures.

Van Gogh pushed the materiality of paint to its limits. Abandoning the polished surfaces of academic painting, he squeezed thick, sticky oils straight from the tube onto the canvas, then attacked them with brush or knife in bold, tactile gestures.

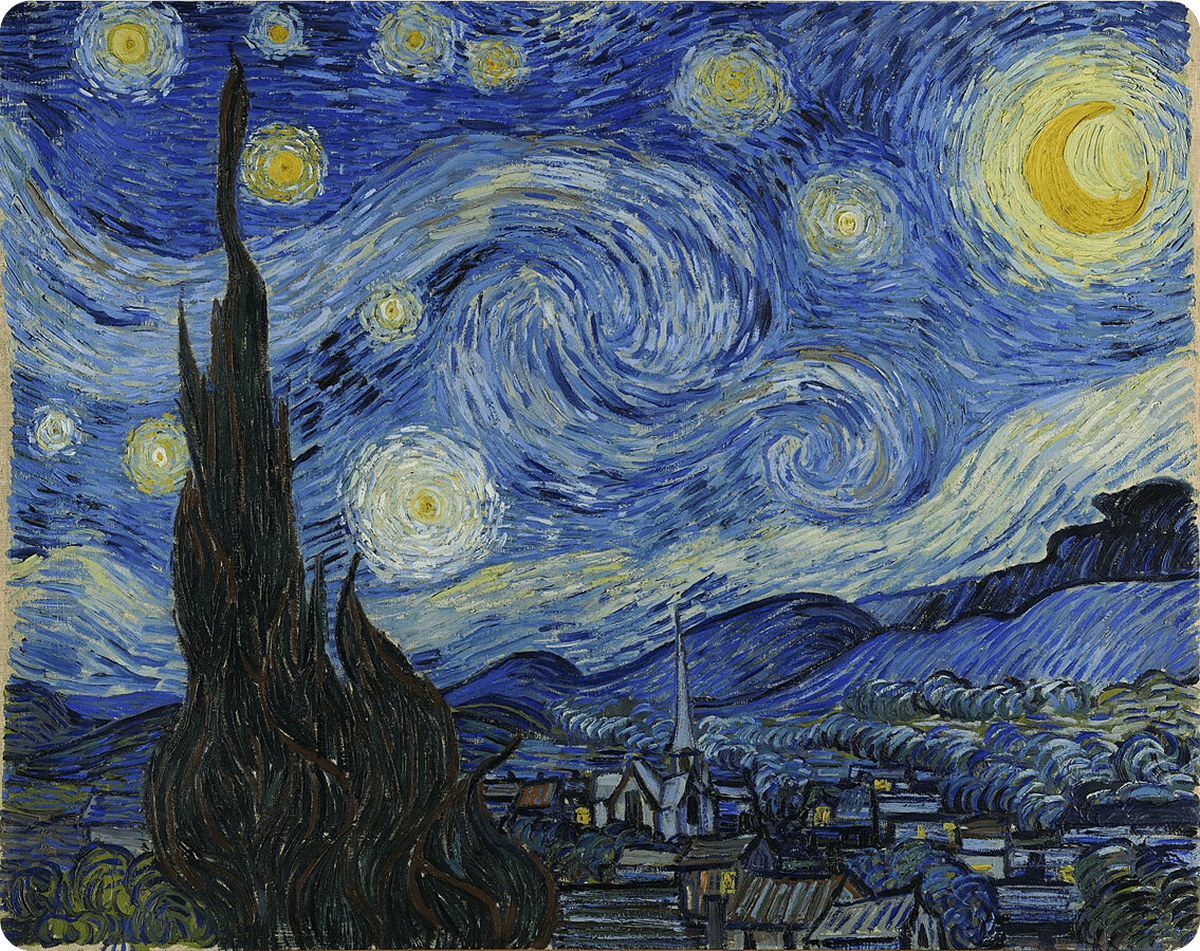

Consider The Starry Night (1889). Its swirling skies and radiant stars rise from the surface like sculpted relief, sometimes several millimetres thick. This 'impasto' technique wasn't mere showmanship; it charged the canvas with energy, turning emotion into physical texture. His brushstrokes became a kind of fingerprint — visceral, directional, unmistakably his. This way of painting reverberated into the 20th century, inspiring Expressionists and Abstract Expressionists alike, from Willem de Kooning to Jackson Pollock, who saw in Van Gogh's strokes the blueprint for emotional and formal liberation.

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York City

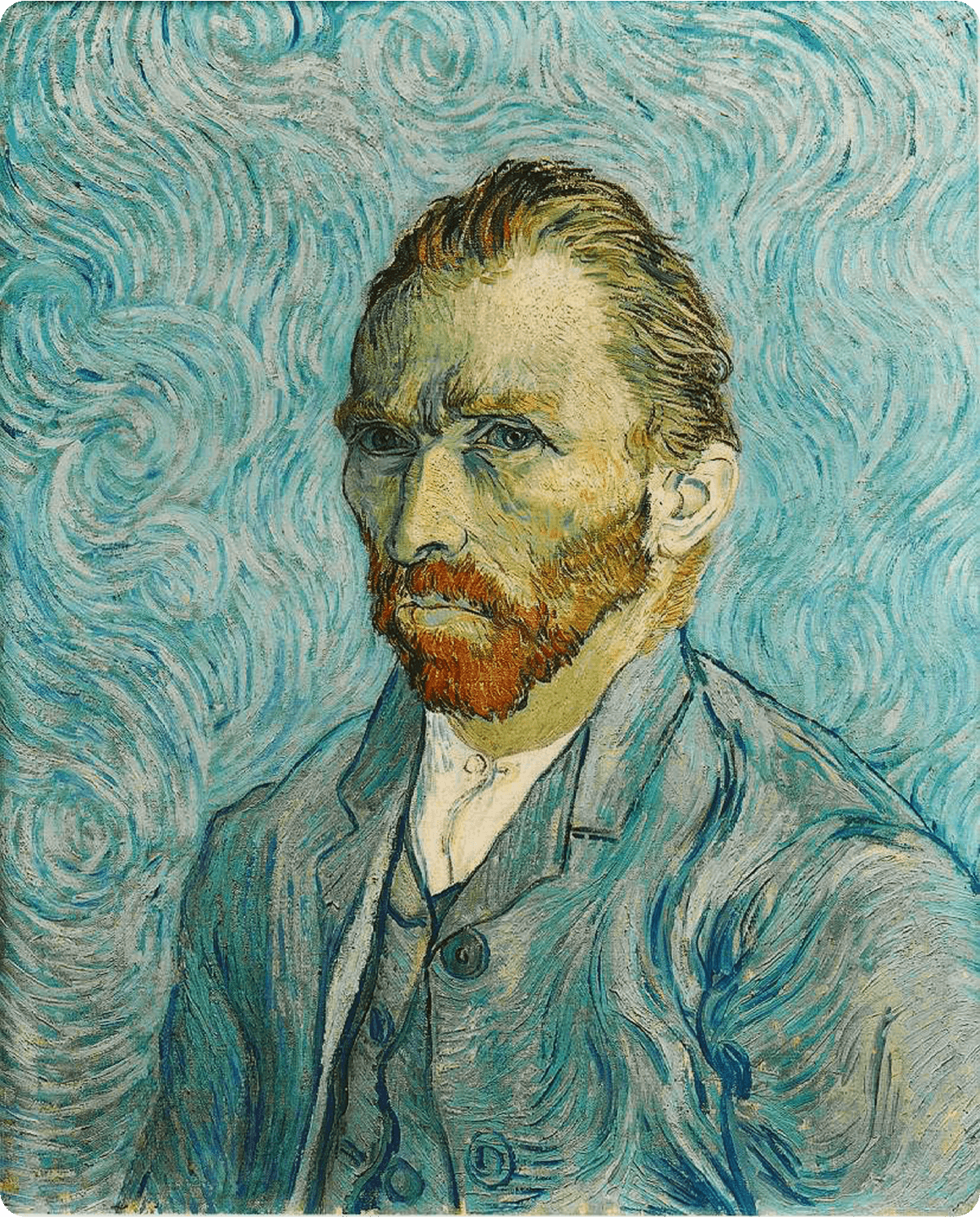

His touch carried motion and intent. In the Wheat Fields series, short, parallel or slanting strokes evoke the wind coursing through ripening grain. In Cypresses, paint flames upwards, as if the trees themselves were alive. In his Self-Portraits, swirling lines coil around the face, revealing a mind in turmoil. Each painting is less a scene than a current of feeling made visible.

Musée d'Orsay, Paris

In the latter half of the 19th century, as Japan opened to global trade during the Meiji era, woodblock prints began arriving in Europe in vast quantities. Their flat planes of vivid colour, bold outlines and unconventional perspectives caused a sensation, sparking a wave of Japonisme across the continent. For artists trained in Renaissance perspective and oil-painting traditions, this was nothing short of a revelation.

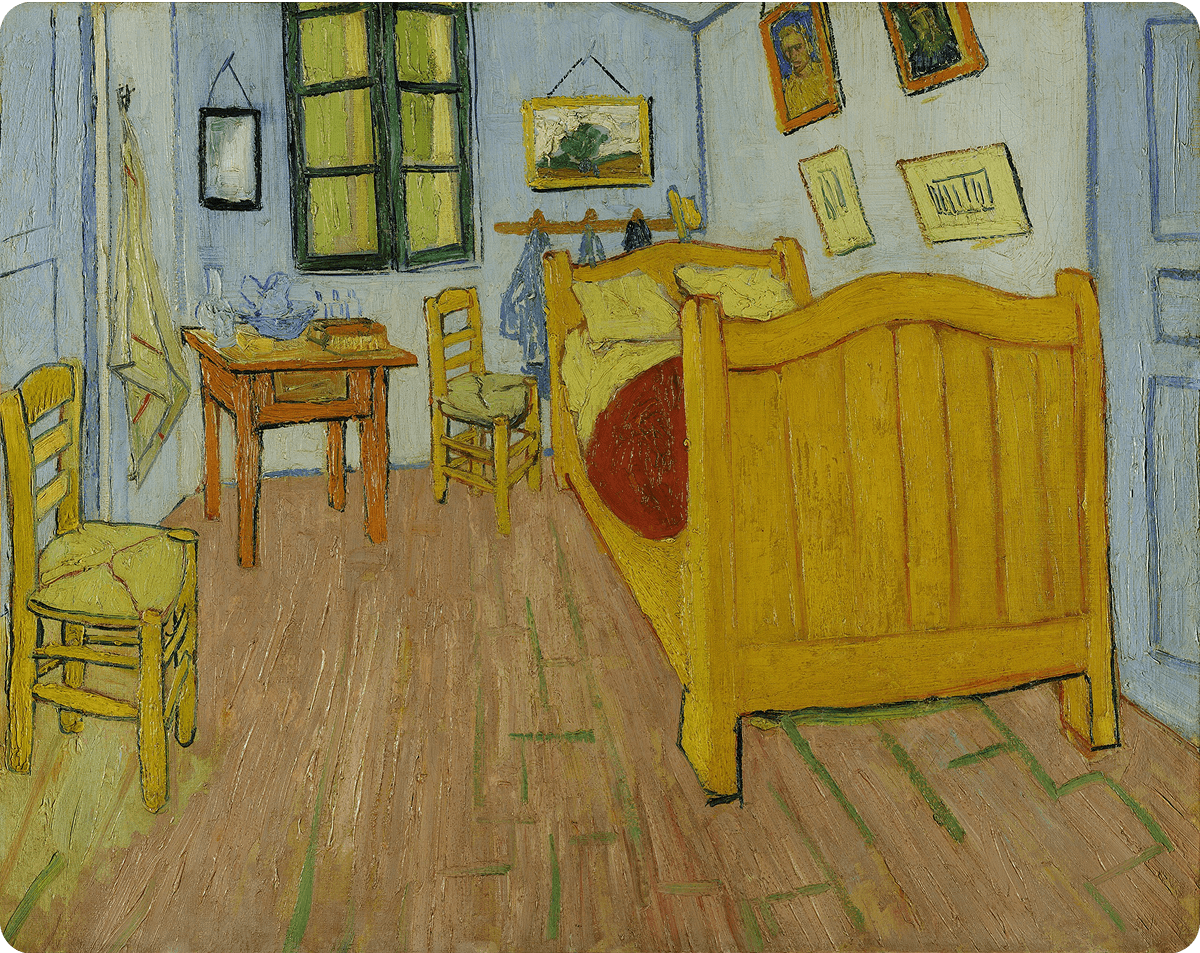

Van Gogh was enthralled. He collected prints obsessively, copied them, and absorbed their logic. Gradually he moved away from deep perspectival space, instead emphasising decorative surface and compositional rhythm. Space was compressed; outlines hardened; the relationship between foreground and background was reimagined to heighten emotional and formal impact.

His Bedroom in Arles (1888) is a perfect example. The floorboards skew, the walls tilt, the furniture seems slightly off-kilter. It's a private room, but also an unsettling one — intimate, yet subtly charged. Van Gogh wasn't simply painting what he saw; he was reshaping space to reflect how it felt.

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

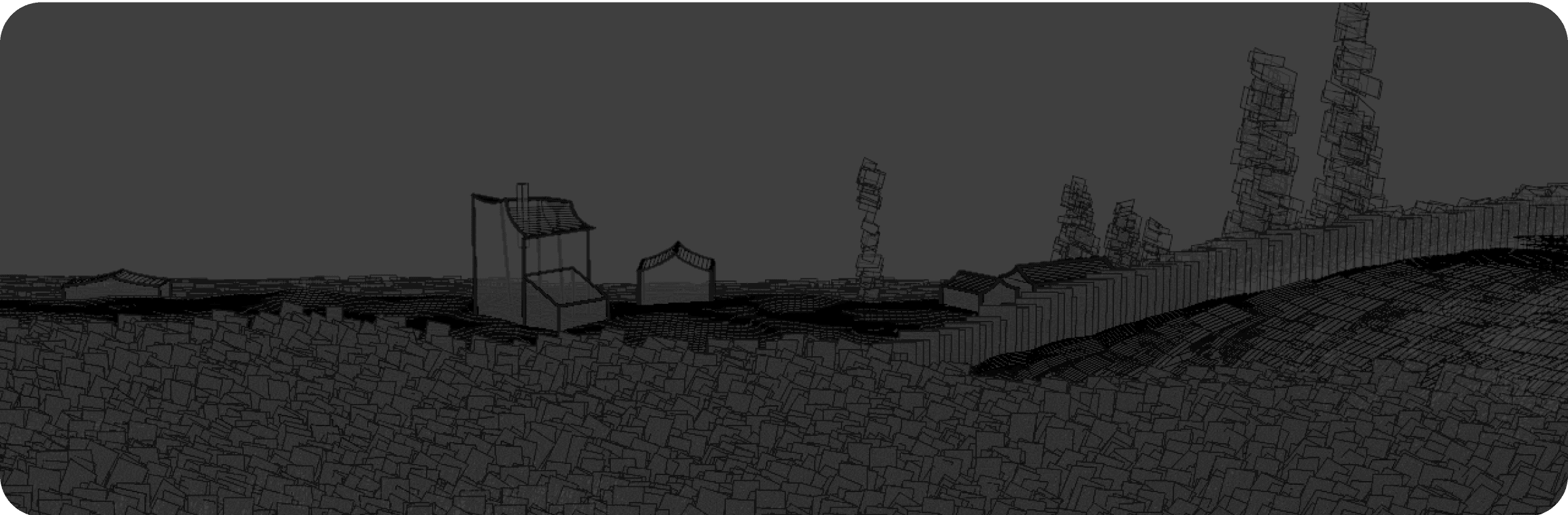

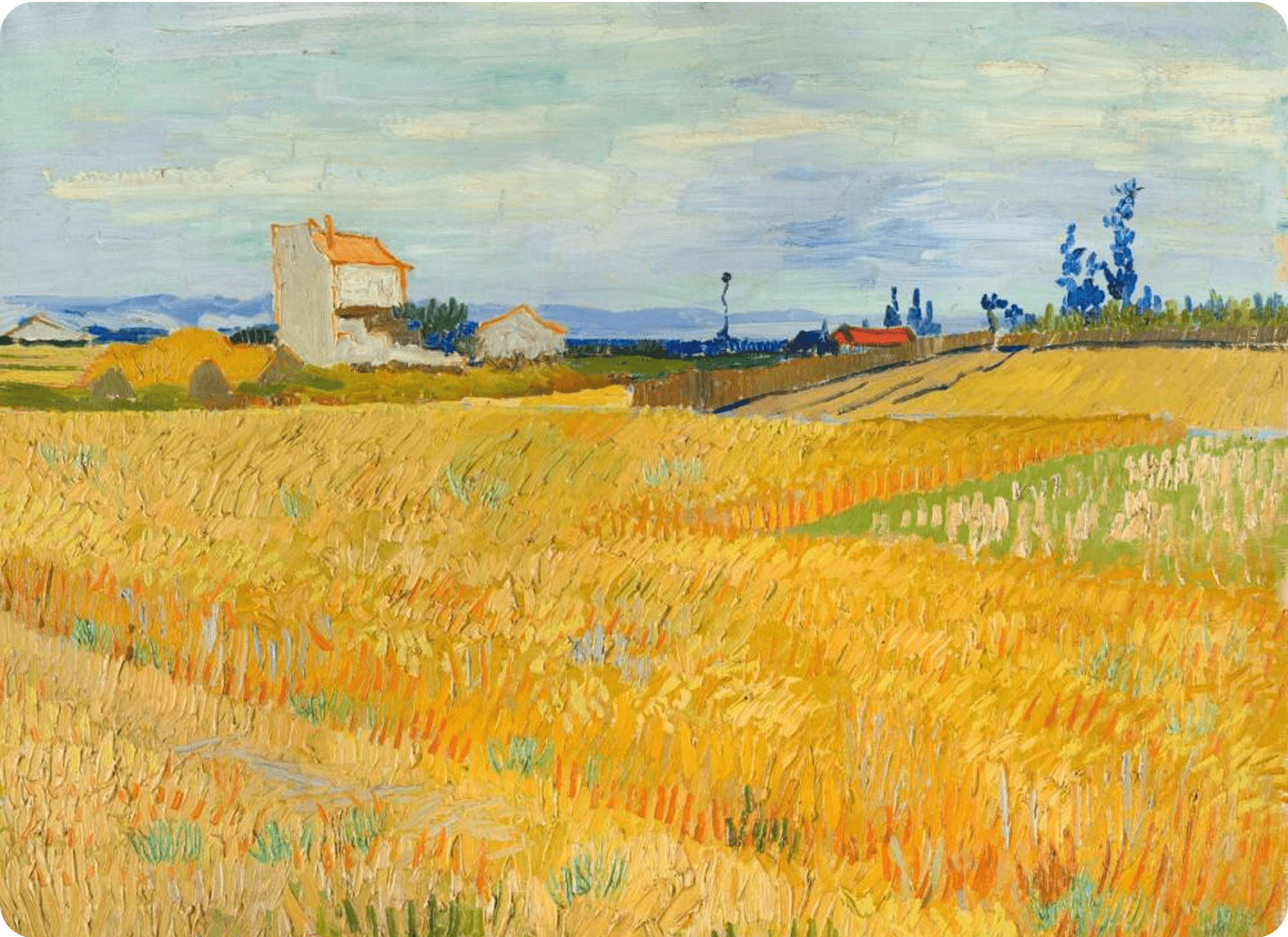

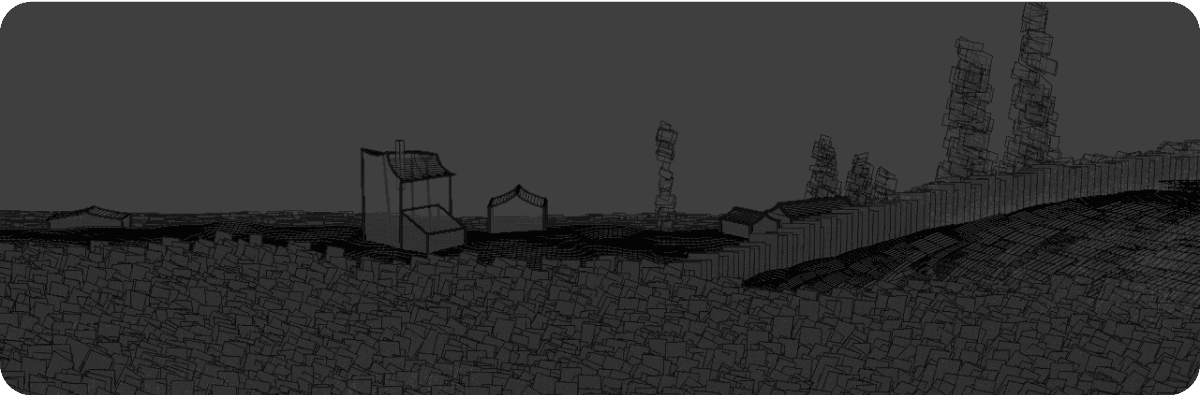

The theme for FydeOS v21 draws directly from Van Gogh's Wheatfield (1888), painted during his time in Arles. It's a landscape at once tangible and dreamlike: golden wheat whipped by the wind, turbulent skies above, a dark horizon beyond. The scene brims with vitality, yet it carries a quiet, almost aching solitude.

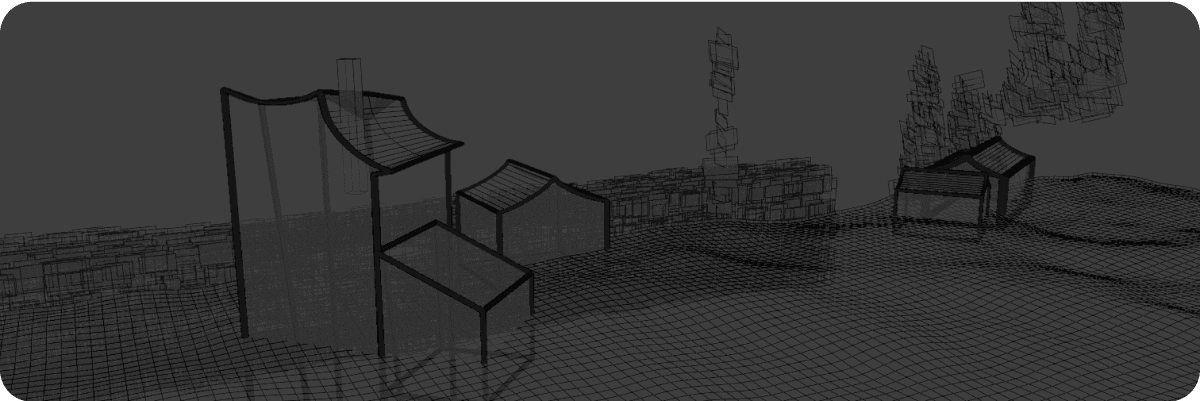

Van Gogh Museum

We set out to capture this distinctive quality using modern 3D modelling — to echo his warped contours, bold outlines and flattened composition, and to breathe new life into a classic. This is more than a visual homage; it's an exploration of a shared spirit: that refusal to accept appearances at face value, that urge to remake perception itself.

To complement this, the FydeOS v21 welcome sound has been reimagined. We borrowed from the score of Loving Vincent (2017), the extraordinary hand-painted animated film that retraces Van Gogh's final days.

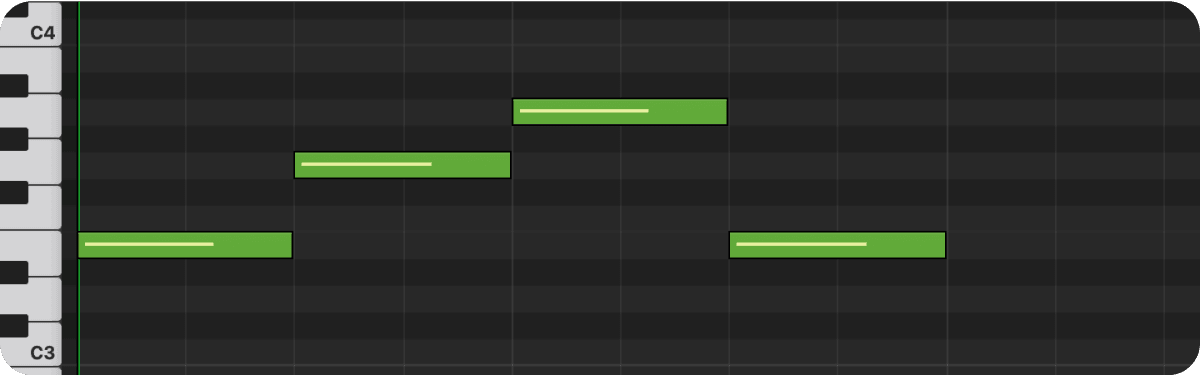

Clint Mansell's Wheatfield With Crows provides the source: a theme built around four simple notes — E, G, A, E — that hover between unease and hope, like wind and light passing over a restless field. It’s a small gesture, but a deliberate one: a way of weaving historical inspiration into the sensory fabric of everyday digital life.

A decade ago, FydeOS was little more than an idea — a seed planted quietly, with modest expectations. Ten years on, it has taken root across the world, finding its place on countless screens and in countless routines. Through this journey, our belief has remained constant: technology should not be a cold instrument, but a medium capable of carrying feeling, intention and warmth. Just as Van Gogh used colour and motion to give shape to his inner world, we hope FydeOS can offer, amid the noise of modern life, a space that feels open, calm and alive — a digital wheatfield where past and future meet, and where technology resonates with the human heart. That, ultimately, is the direction that has guided us all along.