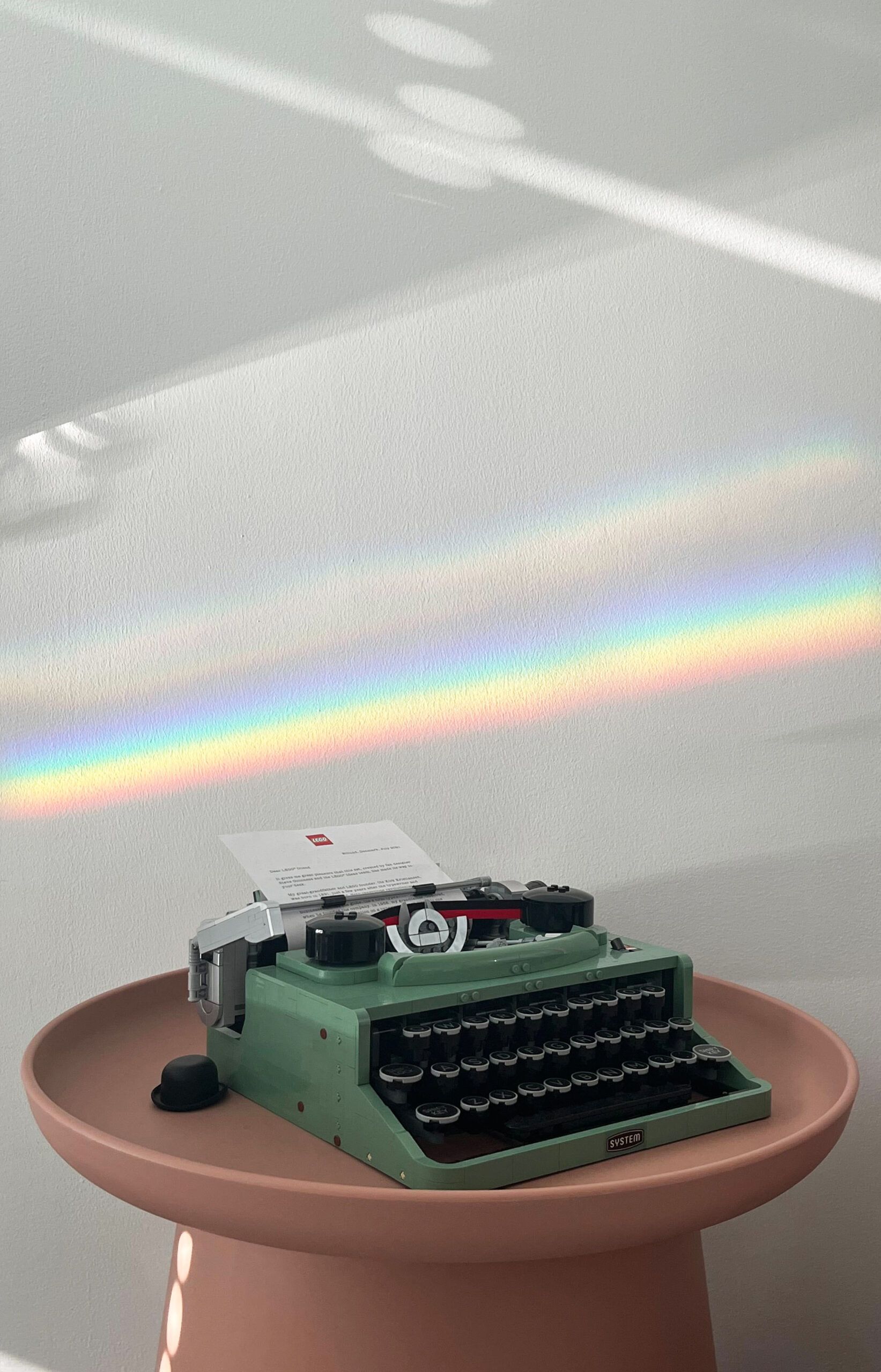

One sweltering morning, a rainbow appeared by chance on our office's prized efficiency tool and mascot - a LEGO typewriter. The soft morning sunlight streamed through the glass of the floor-to-ceiling windows, breaking magically into a spectrum of colours that landed perfectly above it.

Courtesy of the support guy of FydeOS

The phenomenon of light dispersion is truly mesmerising. Our scientific understanding of it dates back to the 17th century when Isaac Newton became the first to systematically study and theorise about it. In his renowned experiment, he used a prism to split sunlight into the seven colours of the spectrum - red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet - before merging them back into white light using a second prism.

Courtesy of The Granger Collection, New York

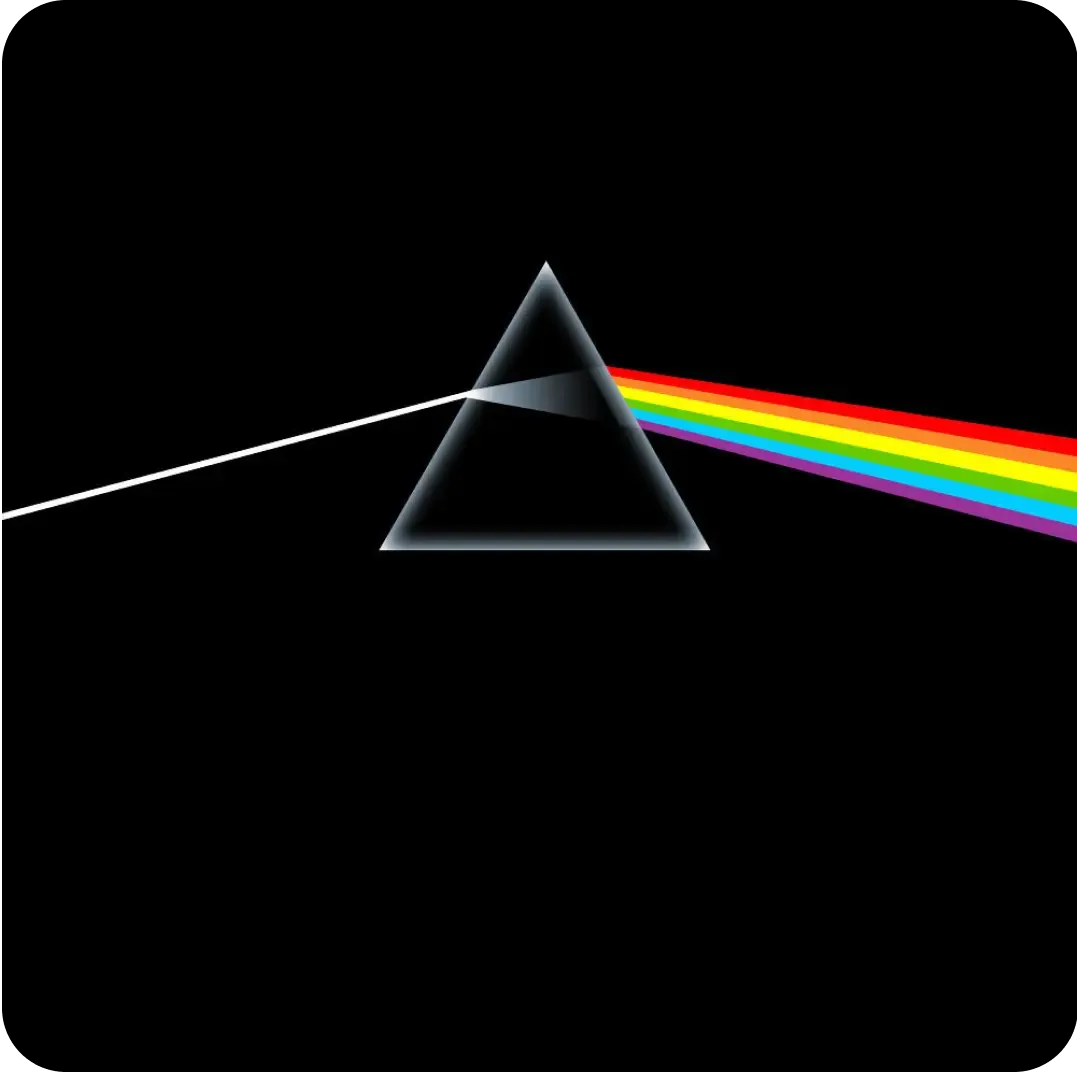

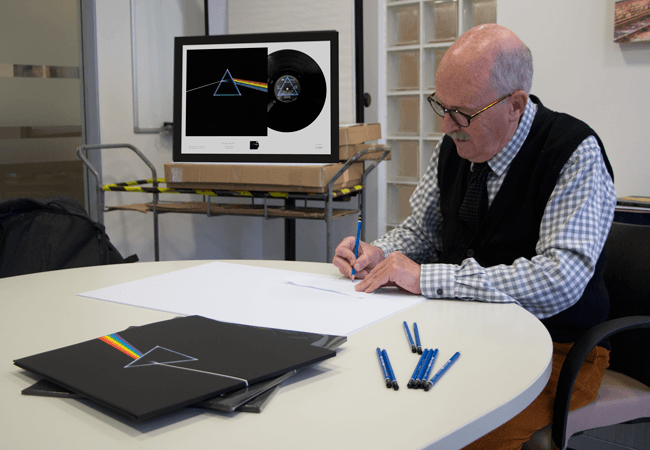

Dispersion happens in an instant, yet even today, commercial physical renderers often require hours to simulate it - and even then, their mathematical accuracy falls short. In this narrow sense, we've yet to catch up with time. But that hasn't dimmed humanity's passion for artistic expression. In 1973, the designer George Hardie immortalised the phenomenon in his cover art for Pink Floyd's album The Dark Side of the Moon.

Printed album cover for the first edition vinyl record

When The Dark Side of the Moon was first released, there were no computers to assist in graphic design. Typography relied on photographic techniques, and designers had to manually assemble or hand-draw their creations. Overlapping designs were achieved using celluloid sheets (an early synthetic resin) where every detail demanded absolute precision.

Today, creating dispersion or thin-film interference effects in renderers is relatively straightforward, with adjustable parameters such as refractive index at our disposal. Yet those nostalgic memories of manual craftsmanship continue to inspire and drive us forward.

On that note, we've updated the welcome sound for our Out-of-Box Experience (OOBE). It draws inspiration from the lyrics of Time on the same Pink Floyd album:

And you run and you run to catch up with the sun, but it's sinking, And racing around to come up behind you again.

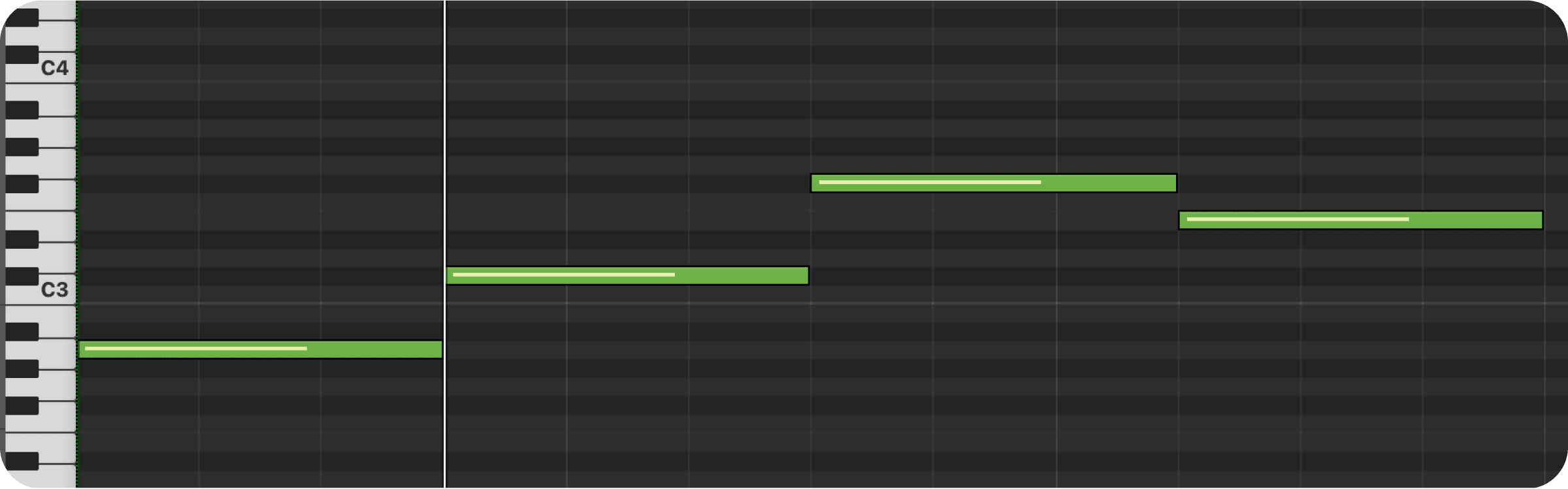

The sound itself is built on an A6 chord: A (root), C# (major third), E (perfect fifth), and F# (major sixth)—a small nod to both the complexity and simplicity of time.

Not long ago, during a meeting with a prominent investor, I was posed a straightforward yet profound question:

There are already so many operating systems in the world. The market doesn't need another one. What makes yours significant?

For a moment, I was speechless.

Nobel laureate Herbert Simon once said that design is a process of continually generating goals and alternatives. Life, too, is an endless series of challenges, each requiring its own solution. Over the past eight years of running a startup, my daily job has been just that - solving the challenge of the day. It feels a bit like playing a video game; you never know what kind of opponent will appear next. All I can do is meet each challenge as it comes.

But that investor's question lingered. What is the purpose of FydeOS?

I've always believed FydeOS has its strengths and unique use cases compared to other operating systems. But does that alone justify its existence? The OS market is fiercely competitive, with many players entering and exiting. Establishing a foothold is no easy feat.

We've grown accustomed to scepticism over the years. Yet as FydeOS has matured through public testing and feature development, more people have embraced it - not just individual users but enterprises too. Perhaps that's the answer: FydeOS doesn't need to prove itself. The market will validate its significance. Time will confirm its worth.

In this game of survival, where only the best remain, my job is simply to persist.

At the end of the meeting, the investor asked me one final question:

What's your greatest strength?

I answered:

Building foundational software demands immense time and effort to see results. Luckily, I am a staunch believer in long-termism.

With that, I dedicate Nostalgic Reflections as a tribute to time itself.